Father's Day Stories from our Neighbors and Friends at The Pinehills

“The older I get, the smarter my father seems to get.” Tim Russert

Father’s Day is this Sunday. It’s a day we celebrate with our dads, grandfathers, uncles and stepfathers, bestowing golf balls, socks, BBQ equipment, and ties. It’s also a day for heartfelt messages, sharing how much they mean to us, and how much we appreciate the wonderful examples they’ve set, the bits of wisdom they (not so) quietly shared, and even the dad jokes.

For Father's Day we have gone back to our Pinehills neighbors who did such a beautiful job celebrating moms, contributors from The Writers Circle and the Wednesday Writers Group who meet at The Pinehills Stonebridge Club: Jonnie Garstka, Peg Ryan, Susan King and Steve Anderson. Enjoy these special memories of their fathers. We laughed...we cried...we related!

Roses, What's not to Love? | by Jonnie Garstka

Flowers? My father loved them. Actually, he loved to look at them. We, his lucky children, got to plant them, fertilize them, de-bug them, deadhead them and seasonally, replace them, with other flowers that needed to be planted, fertilized, de-bugged and deadheaded.

One spring, dad decided we needed a rose arbor. He ordered 40 plants from Jackson and Perkins and had us pace off two parallel rows that would soon be glowing with his flowers, whose colors would melt from red to pink to white to yellow.

After we dug the trenches and put rose dust in the furrows, we planted his babies. Days blended into weeks and there were no buds, no flowers. What we did have was hundreds of Japanese Beetles. Ever the arbitrator, Dad made a contract with us. For every Japanese Beetle we caught, we would get a nickel.

We enthusiastically began to herd those tiny ‘doggies’ into flour sacks. Chris even went to our neighbor’s yards to bag some of theirs. We each made a fortune, sometimes as much as four dollars. And, I firmly believe, Japanese Beetle moms started telling their little larvae to avoid our property.

Back to Dad’s rose grotto, we suspected his beautiful experiment had been planted too close to our six acres of apple trees. Deer, coming in at night for a dessert of Macintosh windfalls, soon found they preferred the gourmet fare of rose petals and, later, rosehips.

Fifty years later, I still have an antipathy towards this special bloom. My husband, Paul, now has American Beauties in his garden. He tends them like babies, with special rose food and lectures about the dangers of beetles.

When he’s not looking, I kick them.

Last Time I Spoke to my Father | by Steve Anderson

The door opened, and the nurse stepped almost in. Long straight black hair, large sympathetic brown eyes, and a smile that told the listener it was easier to agree, “Sorry, I should have stopped in sooner. It’s eleven and well past time to leave. Think about saying goodbye. You can come back in the morning.” She deepened her smile and made eye contact with the four of us, a command, not a request, then stepped back into the hall and silently closed the door.

“Goodbye” and not “Good night,” he might still be here in the morning, but it’s unlikely he’ll understand anything. Since lunch, he hadn’t spoken, edema was racing up his legs, and his labored breath under the oxygen mask stumbled into erratic rhythms.

Covered by a muted gray blanket, he rested on a hospital bed. His head faced the only window. Green or blue walls soften indirect lighting, a room designed for transition. Dad agreed to hospice three days ago and had been here for two, just in time.

We looked at each other. My wife approached the left side of the bed, bent forward, and kissed Dad’s forehead. Gail radiates compassion. She always has. By nature, she makes others comfortable. “Jerry, I love you. Thanks for all you’ve done for everyone.” She paused, took three steps backward, turned, and left the room.

I had known this was coming but hadn’t prepared my last words to Dad. Last year, I muffed it with Mom, “See you on Monday;” she died Sunday morning. But I was 63; we had talked for years, and there wasn’t much left to say. I knew she appreciated my help navigating the last fourteen months, and she understood I thought she was a joy.

Nancy, Brian’s wife, walked past Gail and stopped just short of Dad. She has a bright, expressive face. She’s loving, sincere, and honest. Nancy dropped her shoulders and approached, “Dad, I love you. Thanks for all you’ve done for the family.” Then she kissed him on the forehead, turned, and retreated to the hall.

Last words are for the living, not the dying. They mesh with memories, real or imagined, to help tell a life story: no absolution, confession, or reconciliation, just short words, simple ideas, and a brief conversation.

Brian and I stared at the floor. He and Dad have always been tight; Dad was a machinist, and Brian a manufacturing engineer. They relished projects at the Cape house. The established rituals of the spring opening, turning on the water, igniting the pilot lights, and moving the furniture to the porch. The fall closing the reverse but with a shot of anti-freeze in the pipes. Precise and orderly, instinctively, they know what the other needed.

Brian is Dad’s favorite, son at least. They have a language I’ve never understood, dado cuts, countersinks, 1/8 bits, brass screws, engine rings, gas/oil mixture. The outdoor shower they designed and built twenty-two years ago is still working, perfectly square.

Not to say there haven’t been missteps, flip the light switch in the back bedroom, and you’ll get a shock. They laugh as if it’s a joke; I know they can’t fix it.

Personality’s an issue. Brian is easy, very little drama, straightforward, sharing, and excited to see others. I’m happy to see people I’m glad to see, something I learned from Dad.

Brian ambled past my chair and stood in front of Dad, so he’s next. He moved slowly. Brian reached around the IV tube and took Dad’s hand. He spoke in a slow, measured fashion, not for Dad to hear but so he could finish. “Dad, I love you.” He paused, gathering his emotions, and continued, “You’ve given so much to me. Thanks.” He kissed Dad on the cheek, ran his hand across his head, and quietly left the room crying.

Well, this is awkward. What to say. When four people say the same thing, Steve Anderson’s rule, either the last lacks creativity or something is wrong. Four dinner guests praise only the carrots, likely, the fourth guest is a dullard, or the meal sucks. So, what to say.

An hour and fifteen, maybe more, the trips to the beach house in Fairhaven in the 1956 Pontiac. Three of us in the back seat, brawling and bawling after ten minutes. Dad would begin to tell wild, crazy, fanciful stories to amuse us. Some were mildly inappropriate; Mom’s mother rode a dinosaur to elementary school, which drew a sharp glance from Mom. So, he modified the tale and chuckled, “Actually, Grandma lived close enough to walk to school.” Other fables involved complex storylines, multiple twisted subplots, and complicated human and animal characters.

In the backseat, we listened, worried about lost children, hungry dogs, and leaky boats, and prayed for a happy ending. The resolution was always the same. As soon as he saw the beach house, he’d wrap the legend up. His technique I later learned was Dues ex Machina. A knowing, loving and caring mother solved all problems. He’d look at Mom, and she at him, a quick smile.

I pulled myself up. Maybe last words do matter. I shuffled to the foot of the bed. His chest rose in an irregular rhythm, sometimes halting. What to say.

I touched his chest and bent forward to his left ear.

“Dad, I love you. Thanks for all you’ve done for the family and me.”

Not too original.

I continued, “and thanks for everything you didn’t do.”

Under the mask, he laughed.

I Never Really Knew Him Until Now | by Peg Ryan

He was always called Bill. It was a nickname for William. He was a toolmaker by trade, a husband, father and the oldest brother in a family of 16. He was the kind of guy who could fix anything and as a result, was often called upon by members of the family to help. This he always did willingly. He had a small family of his own, a daughter who was the oldest and a son. Each year, during Bill’s 2-week vacation, the family of 4 would pile into the Studebaker and drive as far as the money in the “Vacation Club” would allow. Unfortunately, his wife Anne died at the age of 60 and Bill was left to fend for himself. With the help of Betty Crocker, he did quite well. His apple pies were always welcome at family gatherings.

One day, during a telephone conversation I had with Bill, he told me a story about his younger days. When he was 18, Bill together with 5 other young men planted all the trees that exist today on Hog Island in Essex, MA. The trees, which stood only 8” high, were brought over from the mainland by barge and planted by hand.

Bill grew up in Ipswich, MA and his community was comprised of Polish, French and Greek immigrant families. Although many of the parents did not speak English, their children had no problem understanding each other. When Bill was 21, he was employed by the Ipswich Civil Court translating Polish! He also spoke French, a little Yiddish, and could communicate in sign language.

There were many phone conversations since the first stories and each conversation revealed yet another fascinating story about Bill’s life. He was so much more than a husband, a father, a son and a sibling. His stories revealed a man so talented, with a wealth of knowledge and a past so very rich in life experiences. Bill died at the age of 97. He was my Father, and I never really knew him until now.

Swimming and Life Lessons | by Jonnie Garstka

My dad promised each of the ten of us that he would toss us off the dock into the Long Island Sound if we hadn’t learned to swim by the time we turned six. We knew it would happen, but happily ignored the fact until our fifth birthdays. Then we would actually try to learn to swim.

In the back of my mind, I knew my mom wouldn’t let me drown. But also, in the back of my mind, I knew my dad would make good his promise. So, I began to teach myself how to swim.

Step One: The Doggie Paddle

If our dogs, who chased their tails all the time thinking someday they would catch them, could do the doggie paddle, so could I.

Step Two: Water Depth

The water below the dock of my dad’s choice was shallow. I could pretend to be swimming while standing up.

Step Three: Fooling Dad

See steps one and two.

As my sixth birthday approached (October 21) I wondered if I would get a reprieve because of my autumnal beginnings … not so, my brother Moe assured me. His birthday is November the sixth and he said he hit the water wearing a sweater and blue jeans.

I was doomed.

All summer long I worked on my crawl. That’s what my mom called it “The Crawl”. With inner tube, without inner tube, the results were the same. I sank like a moss-covered rock. I knew I was going to be the “one less mouth to feed” my mom was always talking about.

Then things changed. I met a girl named Lillian. She was afraid of the water. She didn’t know how to swim, and she was already six! So, I said I would teach her how to swim.

“But first.” I asked. “When is your birthday?”

A Bittersweet Moment | by Susan King

Pictures of my Dad with his beautiful brown eyes never cease to take my breath away. Yet, he never gazed into the camera because his eyes were always focused on us kids - picture after picture, year after year. He had a special place in his heart for children.

Dad and his brother Eddie were part of the Greatest Generation, enlisting for the service in 1942 within a month of each other. Eddie was a bombardier in the Air Force, and my father was a military policeman in the Army.

Two years later, Eddie was shot down in Germany. He was buried in Belgium along with the seven other US soldiers who lost their lives in that fateful plane crash. Dad proudly fought in the Battle of the Bulge and the European and Asiatic Pacific theaters. He never did talk about his great loss or the atrocities of war that he endured.

Forever keeping things on the bright side, he spoke of a young French boy dressed in soiled tatters and a runny little nose. Dad reached into his fatigues, knelt down and handed him a chocolate bar. The little boy looked up with his big brown eyes, gave dad a heartwarming smile and a coy "Merci". I loved to hear this story over and over, and Dad always loved to share it.

Perhaps a simple and sweet teachable moment to his three young kids???

Giving makes you feel better, especially when you're sad.

You never know what people are going through.

Find the positive even in the worst situation.

Candy makes life sweeter.

And don't forget to blow your nose!

Warm Soup | by Jonnie Garstka

If my father were the type to “blow his own horn”, which he was, he would have had a business card that read: Joseph Vincent Lane, Jr., Genius, Father and Chef Extraordinaire, which he did.

The genius he probably was. He had advanced degrees from Fordham, Fordham Law, NYU, and Columbia. He used to tell us, “I got my first long pants when I graduated from Fordham.” Our response to this remark was usually a collective yawn.

I think his measure of success, as a father, probably began with the sheer number of his offspring. Then, the fact that all ten of us went to, and, graduated from, schools of higher learning was added to his list of fatherly accomplishments.

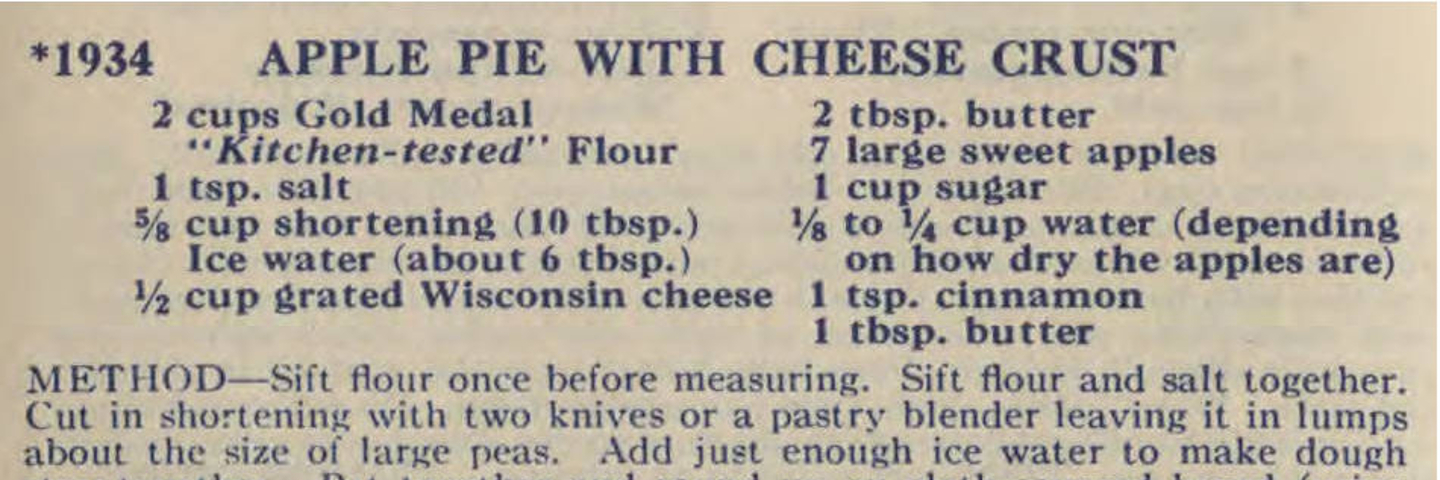

The title of Chef Extraordinaire, which he had magnanimously bestowed upon himself, was another story. Dad made three meals, which he called his chef-d’oeuvres.

The first was scrambled eggs with bacon. Neither the egg, nor the bacon, was ever fully cooked. And, his secret ingredient was Worcestershire Sauce. His Sunday breakfasts were not a favorite with us.

The second prized recipe was Welsh rarebit, a British specialty, and dad’s favorite meal for meatless Friday suppers. It’s ingredients were cheddar cheese, spices, mustard, Worcestershire Sauce and beer, lots and lots of beer. Dad loved it. Our preference for frozen fish sticks on Fridays always puzzled him.

Dad’s third, and, in his expert opinion, greatest performance in the kitchen was his “Day After Thanksgiving Turkey Soup”. He would line up his sous chefs, his children, and have us peeling and chopping celery and carrots, chives and potatoes. Dad’s job was to slice the turkey and add the spices. One year, he decided to enrich the recipe by adding wine. He had a generous hand with it. When it was nearly time for the soup to be soup, Dad sampled the broth. He sipped, grimaced, and sipped again. Then he addressed his hungry apprentices.

“Who wants fish sticks?”